|

تضامنًا مع حق الشعب الفلسطيني |

نواة متكئة

| النواة المتكئة | |

|---|---|

| الاسم العلمي nucleus accumbens septi |

|

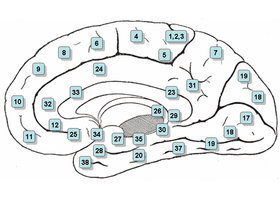

المصطلحات التشريحية موقع المتوسط السطحي، شخص يتجه إلى اليسار. النواة المتكئة هو ما يقرب جدا من منطقة برودمان 34

| |

| تفاصيل | |

| المكونات | قشرة النواة المتكئة النواة المتكئة الأساسية |

| اختصار | NAc أو NAcc |

| الاختصار | NAc أو NAcc |

| جزء من | المسار الوسطي الطرفي العقد القاعدية (المخطط البطيني) |

| معلومات عصبية | braininfo |

| نيوروليكس | Nucleus accumbens |

| ن.ف.م.ط. | + المتكئة&field=entry#TreeA08.186.211.730.885.105.683 A08.186.211.730.885.105.683 |

| دورلاند/إلزيفير | 12580142 |

| تعديل مصدري - تعديل | |

النَّواة المُتَكِئَة (الاسم العلمي: nucleus accumbens septi) هي منطقة مهمة بالمخ.[1][2][3] وهذه المنطقة مسؤولة عن المكافآت بالدماغ البشري،[4][5] وتنشط عند حصول الإنسان على الطعام الجيد أو المال، كما تنشط عند حصول الشخص على سمعة جيدة وثناء ومديح لشخصه.[6] نجد أن من صفات الإنسان الرئيسية سعيه الدائم لتحسين سمعته، وتبين للباحثين أن المنطقة المسؤولة عن المكافآت بالدماغ تكون في قمة نشاطها حين يتعلق الأمر باعتراف الآخرين بالشخص وتقديرهم له وأفعاله. أما ثناؤه على الآخرين فيلعب دورًا أقل في تنشيط تلك المنطقة من دماغه.

مقدمة

الدماغ هو العضو الأكثر تعقيداً في جسم الإنسان. إنّه مسؤول عن كلّ أفكارنا، وأعمالنا، وذكرياتنا، ومشاعرنا، وتجاربنا في العالم. فهذه الكتلة الهلامية من الأنسجة التي يبلغ وزنها حوالى 1.4 كلغ، تحتوي على عددٍ مذهل من الخلايا العصبية أو العصبونات، تحتوي على مئةِ مليارٍ منها. هنالك مناطق فرعية مختلفة تحقق نموا مطردا (أساسية مقابل درع) والمجموعات الفرعية والخلايا العصبية داخل كل منطقة (المستقبلات المماثلة لـD1 مقابل المستقبلات المماثلة لـD2 داخل العصبون الشوكي المتوسط) تكون المسؤولة عن الوظائف المعرفية المختلفة.[7][8] وبالتالي، فإنه له دور كبير في الإدمان.[9][8]

القشرة

قشرة النواة المتكئة هي أساس النواة المتكئة. تشكل القشرة واللب معًا النواة المتكئة بأكملها.

البنية

النواة المتكئة عبارة عن مجموعة من الخلايا العصبية التي توصف بأنها ذات قشرة خارجية ونواة داخلية.[10][11]

داخلياً

تشمل المكونات الداخلية الرئيسية الغلوتاماتية الفعل في النواة المتكئة قشرة الفص الجبهي (وعلى وجه التحديد قشرة الفص الجبهي الظهري وقشرة تحت الحوفي) واللوزة القاعدية الجانبية [English] والحصين البطني

أنواع الخلايا

إن ما يقرب من 95% من الخلايا العصبية في النواة المتكئة عبارة عن خلايا عصبية شوكية متوسطة غابيّة الفعل والتي تُعبر -بشكل أساسي- إما عن مستقبلات مماثلة لـD1 أو مماثلة لـD2.[12] وحوالي 1-2% من أنواع الخلايا العصبية المتبقية عبارة عن عصبونات كولينية بينية شوكية، وأخرى عبارة عن خلايا عصبية بينية غابيّة الفعل.[12]

الكيمياء العصبية

تشتمل بعض النواقل العصبية والمعدلات العصبية والهرمونات التي توَصِّل الإشارة عن طريق مستقبلات داخل النواة المتكئة على:

- الدوبامين: ينطلق الدوبامين في النواة المتكئة بعد التعرض لمحفزات مجزية، بما في ذلك الأدوية الترفيهية مثل الأمفيتامينات والكوكايين والنيكوتين والمورفين.[13][14][15]

- الفينيثيلامين والتيرامين: الفينيثيلامين والتيرامين عبارة عن أمينات نزرة يتم تصنيعها في الخلايا العصبية التي تعبر عن إنزيم هيدروكسيلاز الحمض الأميني العطري (AADC)، والذي يشتمل على جميع الخلايا العصبية الدوبامينية.[16][17][18] يعمل كلا المركبين كمعدلين عصبيين للدوبامين، وينظمان امتصاص وإطلاق الدوبامين في النواة المتكئة عبر التفاعلات مع VMAT2 والمستقبل المرتبط بالأمين النزر 1 في المحطة المحورية للخلايا العصبية الوسطية الطرفية للدوبامين.

- القشريات السكرية والدوبامين: مستقبلات القشريات السكرية هي مستقبلات ستيرويدية القِشْرَانِيّة والوحيدة في قشرة النواة المتكئة. من المعروف حاليًا أن الليفودوبا (L-Dopa) والمنشطات وخاصة القشرانيات السكرية هي المركبات الذاتية الوحيدة المعروفة التي يمكن أن تحفز المشاكل الذهانية؛ لذا فإن فهم السيطرة الهرمونية على الإسقاطات الدوبامينية مع فيما يتعلق بمستقبلات القشريات السكرية يمكن أن يؤدي إلى علاجات جديدة للأعراض الذهنية. أظهرت دراسة حديثة أن تثبيط مستقبلات القشريات السكرية يؤدي إلى انخفاض في إفراز الدوبامين، مما قد يؤدي إلى بحث مستقبلي يشمل الأدوية المضادة للقشرانيات السكرية لتخفيف الأعراض الذهنية.[19]

- غابا: أشارت دراسة حديثة أجريت على الفئران التي استخدمت ناهضات ومناهضات غابا إلى أن مستقبلات غابا A في قشرة النواة المتكئة لها سيطرة مثبطة على سلوك الانعطاف المتأثر بالدوبامين ومستقبلات مستقبل غابا B [English] لها سيطرة مثبطة على تحول سلوك عبر الأسيتيل كولين.[20][21]

- الغلوتامات: أظهرت الدراسات أن الحصار الموضعي للمستقبلات الغلوتاماتية وNMDA في مركز النواة المتكئة يضعف التعلم المكاني.[22] وفي دراسة أخرى تبين أن كلا من NMDA وAMPA -وكلاهما من مستقبلات الجلوتامات- يلعبان أدوارًا مهمة في تنظيم التعلم الفعال.[23]

- السيروتونين أو HT-5: بشكل عام، يكون المشبك الكيميائي العصبي للسيروتونين أكثر وفرة ولديه عدد أكبر من الاتصالات المتشابكة في قشرة النواة المتكئة عن قلب النواة. وهو أيضًا أكبر وأكثر سمكًا ويحتوي على حويصلات أساسية كثيفة أكبر من نظيراتها في قلب النواة المتكئة.[24]

الوظائف

المكافأة والتعزيز

تلعب النواة المتكئة -باعتبارها جزءًا من نظام المكافأة- دورًا مهمًا في معالجة المحفزات المكافئة، وتعزيز المنبهات (مثل الطعام والماء) والرعاية البوية المكافآت التي تعتبر مجزية (كإدمان المخدرات، والجنس، بالإضافة إلى إدمان الرياضة).[25][26][27][28]

تسمح لجسم بأن يشعر باللذة عند تناول الطعام، والشرب، والتناسل، والحصول على الرعاية، ومشاعر اللذة هذه تعزِّز السلوك لكي يتكرَّر. وكلٌّ من هذه السلوكيات مطلوبٌ من أجل استمرارية الجنس البشري. أمَّا المكافآت الاصطناعية، كالمخدّرات، فتوفّر إحساساً فورياً بالمكافأة يليه شعور بالخيبة، وهذا يمنع أيّ مكافأة طبيعية أخرى من أن تكون كاملة. هناك أجزاء معيّنة من الدماغ تنظِّم وظائف محدَّدة، كالحسّ والحركة، بالإضافة إلى المخيخ للتنسيق، والحُصَين للذاكرة. وتتولّى الخلايا العصبية، أو العصبونات، الربط بين منطقةٍ وأخرى عبر مساراتٍ معيّنة، لإرسال المعلومات ودمجها. وقد تكون مسافات امتداد العصبونات قصيرة أو طويلة، مثل مسار المكافأة الذي ينشط عندما يتلقّى الشخص تعزيزاً إيجابياً لسلوكيات، أو مخدّرات معيّنة («مكافأة»). يتكوَّن الجهاز العصبي المركزي من الدماغ والنخاع الشوكي. إنَّها وحدة وظيفية مؤلَّفة من مليارات الخلايا العصبية (العصبونات) التي تتواصل مع بعضها البعض عن طريق الإشارات الكهربائية والكيميائية.

سلوك الأم

وجدت دراسة مصورة بالرنين المغناطيسي الوظيفي (fMRI) التي أُجريَت في عام 2005 أنه عندما كانت أم الفئران موجودة مع صغارها، كانت مناطق الدماغ المشاركة في حالة تعزيز، بما في ذلك النواة المتكئة - كانت نشطة للغاية.[29] تزداد مستويات الدوبامين في النواة المتكئة أثناء سلوك الأم (مع صغارها).[30]

النفور

بالرغم من أن تنشيط العصبون الشوكي المتوسط لمماثل الـD2 في النواة المتكئة له دور في المكافأة، إلا أنه -أيضا- له دور في تعزيز النفور.[31]

النوم بطيء الموجة

الأهمية السريرية

الإدمــان

الإدمان هو حالة تدفع الشخص إلى القيام بسلوكٍ قهري، حتّى عندما تواجهه عواقب سلبية. وهذا السلوك مُعزِّز، أو مُكافِئ. وتتمثّل إحدى سمات الإدمان الرئيسية في فقدان السيطرة لجهة الحدّ من تناول المواد المسبّبة للإدمان. وتشير الأبحاث الأخيرة إلى أنّ مسار المكافأة قد يكون أكثر أهميةً في الرغبة الشديدة المرتبطة بالإدمان، مقارنةً مع المكافأة بحدّ ذاتها. ولقد تعلّم العلماء الكثير عن القواعد الكيميائية-الحيوية، والخلوية، والجزيئية الخاصة بالإدمان؛ فاتّضح أنّ الإدمان هو مرضٌ يصيب الدماغ.[32][33]

- التحمّل: عندما تُستخدَم المخدّرات كالهيروين، بشكلٍ متكرّر مع الوقت، قد ينشأ «التحمّل». والتحمّل يحدث عندما يتوقّف الشخص عن التفاعل مع المخدّر كما كان يحصل معه سابقاً. بتعبيرٍ آخر، يحتاج إلى جرعةٍ أكبر من المخدّر للتوصّل إلى مستوى التفاعل نفسه الذي كان يبلغه في السابق. ومع الاستخدام المتكرّر للهيرويين، تحصل التبعية أيضاً. والتبعية تتطوّر عندما تتكيّف العصبونات مع التعرّض المتكرّر للمخدّر، ولا تعمل بشكلٍ طبيعي إلّا بوجود المخدّر.

- الانسحاب: عندما يتوقّف الشخص عن تناول المخدّر، تحدث عدّة ردود فعل فيسيولوجية. قد تكون خفيفة (مع الكافيين مثلاً)، أو حتّى مميتة (مع الكحول مثلاً). وهذا ما يُعرَف بمتلازمة الانسحاب. وفي حالة الهيرويين مثلاً، قد يكون الانسحاب صعباً جداً، فسوف يعود المدمن إلى استخدام المخدّر مجدّداً لتفادي متلازمة الانسحاب.

الاستئصال

أجري استئصال راديوي للنواة المتكئة، وذلك لعلاج الإدمان وفي محاولة لعلاج الأمراض النفسية. ولكن النتائج لا تزال غير حاسمة ومثيرة للجدل.[34][35]

فاعلية العلاج الوهمي

لقد ثَبُت أن تنشيط النواة المتكئة يُحدِّث تحسبًا لفعالية الدواء عندما يتعاطى أحد علاجًا وهميًا، مما يشير إلى الدور المساهِم للنواة المتكئة في فاعلية الدواء الوهمي.[36][37][38]

صور إضافية

-

مسارات ووظائف الدوبامين والسيروتونين

-

التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي الشريحة الاكليلية تظهر النواة المتكئة المبينة باللون الأحمر

-

التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي سهمي الشكل مع تسليط الضوء (الأحمر) مما يدل على النواة المتكئة.

-

تصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي تظهر فيه النواة المتكئة باللون الأخضر على صور التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي T1 الإكليلية.

-

تصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي تظهر فيه النواة المتكئة باللون الأخضر على صور التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي T1 السهمي.

-

تصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي تظهر فيه النواة المتكئة باللون الأخضر في صور التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي T1 المستعرضة.

انظر أيضًا

المصادر

- ^ Carlson, Neil R. Physiology of Behavior. 11th ed. Boston: Pearson, 2013. Print.

- ^ "Nucleus Accumbens | Location, Structure, Functions & Cells" (بen-US). Archived from the original on 2021-08-30. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

{{استشهاد ويب}}: صيانة الاستشهاد: لغة غير مدعومة (link) - ^ @neurochallenged. "Know your brain: Nucleus Accumbens". @neurochallenged (بEnglish). Archived from the original on 2021-10-27. Retrieved 2022-02-05.

- ^ Day، Jeremy J.؛ Carelli، Regina M. (2007-04). "The Nucleus Accumbens and Pavlovian Reward Learning". The Neuroscientist. ج. 13 ع. 2: 148–159. DOI:10.1177/1073858406295854. ISSN:1073-8584. PMID:17404375. مؤرشف من الأصل في 6 فبراير 2022.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: تحقق من التاريخ في:|تاريخ=(مساعدة) والوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ Knutson, Brian; Adams, Charles M.; Fong, Grace W.; Hommer, Daniel (15 Aug 2001). "Anticipation of Increasing Monetary Reward Selectively Recruits Nucleus Accumbens". The Journal of Neuroscience (بEnglish). 21 (16): RC159–RC159. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0002.2001. ISSN:0270-6474. Archived from the original on 2021-07-03.

- ^ Nucleus Accumbens نسخة محفوظة 2 أكتوبر 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- ^ Wenzel، JM؛ Rauscher، NA؛ Cheer، JF؛ Oleson، EB (2015). "A role for phasic dopamine release within the nucleus accumbens in encoding aversion: a review of the neurochemical literature". ACS Chem Neurosci. ج. 6 ع. 1: 16–26. DOI:10.1021/cn500255p. PMID:25491156.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: الوسيط غير المعروف|name-list-format=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|name-list-style=(مساعدة) - ^ أ ب

Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 10: Neural and Neuroendocrine Control of the Internal Milieu". في Sydor A, Brown RY (المحرر). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (ط. 2nd). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ص. 266.

Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with reward.

{{استشهاد بكتاب}}: صيانة الاستشهاد: أسماء متعددة: قائمة المؤلفين (link) - ^

Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (المحرر). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (ط. 2nd). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ص. 147–148, 367, 376.

VTA DA neurons play a critical role in motivation, reward-related behavior (Chapter 15), attention, and multiple forms of memory. This organization of the DA system, wide projection from a limited number of cell bodies, permits coordinated responses to potent new rewards. Thus, acting in diverse terminal fields, dopamine confers motivational salience ("wanting") on the reward itself or associated cues (nucleus accumbens shell region), updates the value placed on different goals in light of this new experience (orbital prefrontal cortex), helps consolidate multiple forms of memory (amygdala and hippocampus), and encodes new motor programs that will facilitate obtaining this reward in the future (nucleus accumbens core region and dorsal striatum). In this example, dopamine modulates the processing of sensorimotor information in diverse neural circuits to maximize the ability of the organism to obtain future rewards. ...

The brain reward circuitry that is targeted by addictive drugs normally mediates the pleasure and strengthening of behaviors associated with natural reinforcers, such as food, water, and sexual contact. Dopamine neurons in the VTA are activated by food and water, and dopamine release in the NAc is stimulated by the presence of natural reinforcers, such as food, water, or a sexual partner. ...

The NAc and VTA are central components of the circuitry underlying reward and memory of reward. As previously mentioned, the activity of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA appears to be linked to reward prediction. The NAc is involved in learning associated with reinforcement and the modulation of motoric responses to stimuli that satisfy internal homeostatic needs. The shell of the NAc appears to be particularly important to initial drug actions within reward circuitry; addictive drugs appear to have a greater effect on dopamine release in the shell than in the core of the NAc.{{استشهاد بكتاب}}: صيانة الاستشهاد: أسماء متعددة: قائمة المؤلفين (link) - ^ Zoli، M.؛ Cintra، A.؛ Zini، I.؛ Hersh، L. B.؛ Gustafsson، J. A.؛ Fuxe، K.؛ Agnati، L. F. (1990-09). "Nerve cell clusters in dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens of the male rat demonstrated by glucocorticoid receptor immunoreactivity". Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. ج. 3 ع. 5: 355–366. ISSN:0891-0618. PMID:1977414. مؤرشف من الأصل في 25 مايو 2021.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: تحقق من التاريخ في:|تاريخ=(مساعدة) - ^ Demetre, D. C. (22 Jun 2011). "What Is The Nucleus Accumbens?". sciencebeta.com (بEnglish). Archived from the original on 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- ^ أ ب Robison، Alfred J.؛ Nestler، Eric J. (12 أكتوبر 2011). "Transcriptional and Epigenetic Mechanisms of Addiction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. ج. 12 ع. 11: 623–637. DOI:10.1038/nrn3111. ISSN:1471-003X. PMID:21989194. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2021-08-14.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: الوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ Pontieri، F E؛ Tanda، G؛ Di Chiara، G (19 ديسمبر 1995). "Intravenous cocaine, morphine, and amphetamine preferentially increase extracellular dopamine in the "shell" as compared with the "core" of the rat nucleus accumbens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. ج. 92 ع. 26: 12304–12308. ISSN:0027-8424. PMID:8618890. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2021-03-10.

- ^ "Elsevier: Article Locator Error - Article Not Recognized". linkinghub.elsevier.com. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2022-01-31. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2022-01-31.

- ^ Chen، Yuan-Hao؛ Huang، Eagle Yi-Kung؛ Kuo، Tung-Tai؛ Hoffer، Barry J.؛ Miller، Jonathan؛ Chou، Yu-Ching؛ Chiang، Yung-Hsiao (21 أبريل 2017). "Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens is altered following traumatic brain injury". Neuroscience. ج. 348: 180–190. DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.02.001. ISSN:1873-7544. PMID:28196657. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2022-02-02.

- ^ Parthasarathy، Anutthaman؛ Cross، Penelope J.؛ Dobson، Renwick C. J.؛ Adams، Lily E.؛ Savka، Michael A.؛ Hudson، André O. (2018). "A Three-Ring Circus: Metabolism of the Three Proteogenic Aromatic Amino Acids and Their Role in the Health of Plants and Animals". Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. ج. 5. DOI:10.3389/fmolb.2018.00029/full. ISSN:2296-889X. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2021-11-14.

- ^ Karasawa، Nobuyuki؛ Hayashi، Motoharu؛ Yamada، Keiki؛ Nagatsu، Ikuko؛ Iwasa، Mineo؛ Takeuchi، Terumi؛ Uematsu، Mitsutoshi؛ Watanabe، Kazuko؛ Onozuka، Minoru (3 يوليو 2007). "Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH)- and Aromatic-L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase (AADC)-Immunoreactive Neurons of the Common Marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) Brain: An Immunohistochemical Analysis". Acta Histochemica et Cytochemica. ج. 40 ع. 3: 83–92. DOI:10.1267/ahc.06019. ISSN:0044-5991. PMID:17653300. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2022-02-02.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: الوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ Eiden، Lee E.؛ Weihe، Eberhard (2011-1). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. ج. 1216: 86–98. DOI:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. ISSN:0077-8923. PMID:21272013. مؤرشف من الأصل في 19 نوفمبر 2021.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: تحقق من التاريخ في:|تاريخ=(مساعدة) والوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ Barrot, Michel; Marinelli, Michela; Abrous, Djoher Nora; Rougé-Pont, Françoise; Moal, Michel Le; Piazza, Pier Vincenzo (2000). "The dopaminergic hyper-responsiveness of the shell of the nucleus accumbens is hormone-dependent". European Journal of Neuroscience (بEnglish). 12 (3): 973–979. DOI:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00996.x. ISSN:1460-9568. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08.

- ^ Shirayama، Yukihiko؛ Chaki، Shigeyuki (2006-10). "Neurochemistry of the Nucleus Accumbens and its Relevance to Depression and Antidepressant Action in Rodents". Current Neuropharmacology. ج. 4 ع. 4: 277–291. ISSN:1570-159X. PMID:18654637. مؤرشف من الأصل في 25 مايو 2021.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: تحقق من التاريخ في:|تاريخ=(مساعدة) والوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ Akiyama, Gaku; Ikeda, Hiroko; Matsuzaki, Satoshi; Sato, Michiko; Moribe, Shoko; Koshikawa, Noriaki; Cools, Alexander R. (1 Jun 2004). "GABAA and GABAB receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell differentially modulate dopamine and acetylcholine receptor-mediated turning behaviour". Neuropharmacology (بEnglish). 46 (8): 1082–1088. DOI:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.02.007. ISSN:0028-3908. Archived from the original on 2019-05-13.

- ^ Smith-Roe, Stephanie L.; Sadeghian, Kenneth; Kelley, Ann E. (1999). "Spatial learning and performance in the radial arm maze is impaired after N-methyl-{d}-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockade in striatal subregions". Behavioral Neuroscience (بEnglish). 113 (4): 703–717. DOI:10.1037/0735-7044.113.4.703. ISSN:1939-0084. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08.

- ^ Giertler, Christian; Bohn, Ines; Hauber, Wolfgang (2005). "Involvement of NMDA and AMPA/KA receptors in the nucleus accumbens core in instrumental learning guided by reward-predictive cues". European Journal of Neuroscience (بEnglish). 21 (6): 1689–1702. DOI:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03983.x. ISSN:1460-9568. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08.

- ^ Belmer، Arnauld؛ Klenowski، Paul M.؛ Patkar، Omkar L.؛ Bartlett، Selena E. (2017). "Mapping the connectivity of serotonin transporter immunoreactive axons to excitatory and inhibitory neurochemical synapses in the mouse limbic brain". Brain Structure & Function. ج. 222 ع. 3: 1297–1314. DOI:10.1007/s00429-016-1278-x. ISSN:1863-2653. PMID:27485750. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2022-02-03.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: الوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ LeGates, Tara A.; Kvarta, Mark D.; Tooley, Jessica R.; Francis, T. Chase; Lobo, Mary Kay; Creed, Meaghan C.; Thompson, Scott M. (2018-12). "Reward behaviour is regulated by the strength of hippocampus–nucleus accumbens synapses". Nature (بEnglish). 564 (7735): 258–262. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0740-8. ISSN:1476-4687. Archived from the original on 17 أغسطس 2021.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: تحقق من التاريخ في:|تاريخ=(help) - ^ Di Chiara, Gaetano; Bassareo, Valentina; Fenu, Sandro; De Luca, Maria Antonietta; Spina, Liliana; Cadoni, Cristina; Acquas, Elio; Carboni, Ezio; Valentini, Valentina (1 Jan 2004). "Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection". Neuropharmacology. Frontiers in Addiction Research: Celebrating the 30th Anniversary of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. (بEnglish). 47: 227–241. DOI:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.032. ISSN:0028-3908. Archived from the original on 2019-07-25.

- ^ Scofield, M. D.; Heinsbroek, J. A.; Gipson, C. D.; Kupchik, Y. M.; Spencer, S.; Smith, A. C. W.; Roberts-Wolfe, D.; Kalivas, P. W. (1 Jul 2016). "The Nucleus Accumbens: Mechanisms of Addiction across Drug Classes Reflect the Importance of Glutamate Homeostasis". Pharmacological Reviews (بEnglish). 68 (3): 816–871. DOI:10.1124/pr.116.012484. ISSN:0031-6997. PMID:27363441. Archived from the original on 2021-10-29.

- ^ Cadet, Jean Lud (15 Oct 2021). "Sex in the Nucleus Accumbens: ΔFosB, Addiction, and Affective States". Biological Psychiatry (بالإنجليزية). 90 (8): 508–510. DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.08.002. ISSN:0006-3223. PMID:34556203. Archived from the original on 2022-02-15.

- ^ Ferris، Craig F.؛ Kulkarni، Praveen؛ Sullivan، John M.؛ Harder، Josie A.؛ Messenger، Tara L.؛ Febo، Marcelo (5 يناير 2005). "Pup Suckling Is More Rewarding Than Cocaine: Evidence from Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Three-Dimensional Computational Analysis". The Journal of Neuroscience. ج. 25 ع. 1: 149–156. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3156-04.2005. ISSN:0270-6474. PMID:15634776. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2021-03-08.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: الوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ Numan, Michael (2007). "Motivational systems and the neural circuitry of maternal behavior in the rat". Developmental Psychobiology (بEnglish). 49 (1): 12–21. DOI:10.1002/dev.20198. ISSN:1098-2302. Archived from the original on 2022-02-02.

- ^ Calipari، Erin S.؛ Bagot، Rosemary C.؛ Purushothaman، Immanuel؛ Davidson، Thomas J.؛ Yorgason، Jordan T.؛ Peña، Catherine J.؛ Walker، Deena M.؛ Pirpinias، Stephen T.؛ Guise، Kevin G. (8 مارس 2016). "In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. ج. 113 ع. 10: 2726–2731. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1521238113. ISSN:0027-8424. PMID:26831103. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2021-03-09.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: الوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة) - ^ Hyman، Steven E.؛ Malenka، Robert C.؛ Nestler، Eric J. (2006). "Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory". Annual Review of Neuroscience. ج. 29: 565–98. DOI:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. PMID:16776597.

- ^ Steiner، Heinz؛ Van Waes، Vincent (2013). "Addiction-related gene regulation: Risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. Other psychostimulants". Progress in Neurobiology. ج. 100: 60–80. DOI:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001. PMC:3525776. PMID:23085425.

- ^ Nicholas (28 Apr 2008). "China Bans Irreversible Brain Procedure". Wall Street Journal (بen-US). ISSN:0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

{{استشهاد بخبر}}: صيانة الاستشهاد: لغة غير مدعومة (link) - ^ Maia (13 Dec 2012). "Controversial Surgery for Addiction Burns Away Brain's Pleasure Center". Time (بen-US). ISSN:0040-781X. Archived from the original on 2022-01-28. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

{{استشهاد بخبر}}: صيانة الاستشهاد: لغة غير مدعومة (link) - ^ Scott, David J.; Stohler, Christian S.; Egnatuk, Christine M.; Wang, Heng; Koeppe, Robert A.; Zubieta, Jon-Kar (19 Jul 2007). "Individual Differences in Reward Responding Explain Placebo-Induced Expectations and Effects". Neuron (بالإنجليزية). 55 (2): 325–336. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.028. ISSN:0896-6273. PMID:17640532. Archived from the original on 2013-06-23.

- ^ Hopkin, Michael (18 Jul 2007). "Revealed: how the mind processes placebo effect". Nature (بEnglish). DOI:10.1038/news070716-10. ISSN:1476-4687. Archived from the original on 2022-03-14.

- ^ Zubieta، Jon-Kar؛ Stohler، Christian S. (2009-03). "Neurobiological Mechanisms of Placebo Responses". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. ج. 1156 ع. 1: 198–210. DOI:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04424.x. ISSN:0077-8923. PMID:19338509. مؤرشف من الأصل في 20 يناير 2022.

{{استشهاد بدورية محكمة}}: تحقق من التاريخ في:|تاريخ=(مساعدة) والوسيط غير المعروف|PMCID=تم تجاهله يقترح استخدام|pmc=(مساعدة)

وصلات خارجية

- دور النواة المتكئة في دائرة المكافأة . Part of "The Brain From Top to Bottom." at thebrain.mcgill.ca

- Nucleus Accumbens – Cell Centered Database

- صور لشريحة دماغية مصبوغة تُشمل "nucleus%20accumbens" على مشروع برين مابز [English]

| في كومنز صور وملفات عن: نواة متكئة |